Lecturing on Zoom is a poor substitute for speaking to a live audience, but it’s something I’ve got quite used to now. Just before lockdown I led a study day on Seamus Heaney: sixty students and I, all of us absorbed in shaping and sharing our responses to the language and life of a remarkable poet. I couldn’t have done that on Zoom. The subjects on which I have spoken since Lockdown #1 include Venice, stained glass, the pelican in art, a potted history of punting, and portraits in the collections of The Wilson, Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum. In the run-up to Christmas I lectured twice on ‘Looking at the Nativity Anew’ in which I discussed representations of the Nativity story – broadly, from the Annunciation to the Flight into Egypt – in painting, sculpture and stained glass from the 14th century to the present day.

My favourite Christmas card received this year is one published by the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. At first glance it’s a touching scene – humorous, even – found in the 15th century Besançon Book of Hours. Had it arrived while I was preparing my Nativity lecture I should certainly have included it. The title is ‘Nativity, Virgin Reading’ (Fitzwilliam Ms.69 f.48r) and indeed the chief surprise of the scene is that Mary is emphatically not nursing her newborn child: she has delegated that job to Joseph while she sits comfortably in bed, propped up against a plump bolster, absorbed in a book. She wears an arresting canary-coloured kirtle (none of your traditional blue or red) and a white headdress tucked back carefully to reveal a neatly-curled blonde ringlet. The conventional Virgin Mother she isn’t.

Even more surprising than the clothes she wears is her scarlet, gold-spotted coverlet. This blanket steals the show. Did she and Joseph bring it with them, for use in just such an emergency? It’s almost possible: the hem of Joseph’s blue gown matches the hem of Mary’s red blanket. However, Joseph’s clothes (especially the homespun woollen cowl around his shoulders) are less sophisticated than his wife’s. So, apparently, are his manners: he hasn’t taken off his boots before planting his feet on the edge of Mary’s blanket.

It is difficult to identify the stable space as represented here: is it the modest wooden framework at the head of Mary’s bed? Is Joseph sitting on grass? What are we to make of the elaborate screen in the background, or the grey wall in front of it? Is the wattle-fenced enclosure, where the ox and ass1 have their ringside view of the holy family, the real stable? There is no sign of a manger: all the ass appears to be eating is Joseph’s halo.

These observations aren’t meant to be flippant. The more I study this picture the more puzzling it becomes. Beneath Mary’s bed is a scrubby little plant. There are of course flowers traditionally associated with Mary; but this apology for a lily seems an almost ironic comment on a scene where, frankly everything is turned on its head. Mary relaxes in the manner of an indulged wife able to leave childcare to others; she shows no interest in her newborn son or her husband, squatting as they are on the ground at the foot of her bed. Usually, images of the Nativity depict Mary as a mother absorbed in the baby to whom she has just given birth. But not here. Have you ever seen the Nativity depicted like this anywhere else?

Actually I have: at Magdeburg Cathedral in a carved panel on the end of a 14th century choir stall. (The guidebook dates it with surprising precision to 1363). Mary, sleeping centre-stage, dominates this scene both physically – she is more than twice the size of anyone else in this rather crowded image – and because she is fast asleep. Her head is propped comfortably against her right hand as she lies on an amply-draped couch, and her face betrays simple contentment: her child is born, she has fulfilled the task she was given; let someone else take over, for the time being at least. And someone else is, for a nurse maid (bottom left) is giving an apprehensive Jesus his first bath.

Joseph, altogether upstaged, is also asleep. His head lies against his elbow which rests on a curious Gothic structure. Does this enclosure really indicate the manger? Here are the ox and ass – rather inexpertly carved, it must be said. I am sure the figure of Mary is the work of a master holzschnitzler: from head to toe she is clothed in loosely flowing garments which nevertheless suggest powerfully the physical presence of a body in repose. The other figures and animals look, frankly, like apprentice work: The scroll held by the three angels is crudely shaped2; so are the arms and hands of the angels themselves. Still, the two shepherds (on the left) have a certain vigour. The cowled figure being reassured by an angel3 has an expressive face and holds a staff that could easily double as a cudgel. I like the cross-legged fellow, so absorbed in playing his own music he appears oblivious to the song of the angels. Traditionally, one of the shepherds always carries a bagpipe: in a 16th century carol, Wat, the ‘gud herdés boy’, offers his to the child in the manger:

‘Jesu, I offer to thee here my pipe,

My skirt, my tar-box,4 and my scrip;

Home to my felowes now will I skip,

And also look unto my shepe.’

Ut hoy!

For in his pipe he made so much joy.

'Jolly Wat' (Anon)5

I have to keep reminding myself it is all too easy to underestimate medieval artists and to be fooled by their apparent innocence. But I find the freshness of their vision, their ability to present scenes and situations in ways so strange to us, sometimes disconcerting. What have they seen that we, for all our self-assured sophistication, may have missed? A brief dismissive smile won’t do. We have to keep looking.

Adrian Barlow

Illustrations:(i) Christmas card from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (photo: the author)

(ii) 14th century carved panel from Magdeburg Cathedral (postcard, purchased from Cathedral shop)

Footnotes:

1) The ox and ass are essential components of Nativity iconography, but they are never mentioned in New Testament descriptions of the birth of Christ. Different explanations of their significance can be found: my preference is for the argument that the ox is a ‘clean’ animal in Rabbinical tradition and teaching whereas the ass is ‘unclean’; hence side by side in the stable they represent Jew and Gentile together witnessing the birth of Salvator Mundi, [‘the saviour of the world’].

2) The length of this scroll suggests that it would have contained the text Gloria in Excelsis Deo [‘Glory to God in the Highest’].

3) The short scroll carried by the angel addressing the startled shepherd who has picked up his cudgel would have been inscribed Noli timere [‘Fear Not’]. In 2013, it was this Latin injunction that the poet Seamus Heaney texted from his hospital bed to his wife, as his last words.

4) Tar-box: a small container once carried by shepherds. It contained an ointment (‘tar’) made from the ash of pinewood mixed with pine sap. This was used as a salve for scratches or scabs on sheep.

5) This carol, Jolly Wat, can be found in the Oxford Book of Ballads (ed. Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, 1910, p.439).

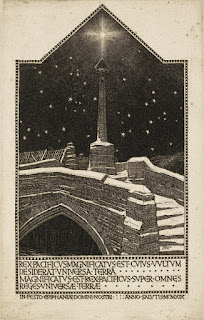

My previous post, A Christmas Card?, discusses a design for a card by the Arts & Crafts artist, Frederick Landseer Griggs. This is one of a series of discussions in which I have focused on works of Art in the collections of The Wilson, Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum. To read any of these, click here.