Don’t underestimate Frederick Landseer Griggs (1873-1938). The following description of him is not mine:

While Griggs trained initially as an architect in the Arts & Crafts tradition under C. E. Mallows, it is as a draughtsman and printer-maker that he is best known. His unsurpassed contemporary reputation as an etcher was acknowledged by his election to the Royal Academy in 1931. Demonstrating an equal mastery of meticulous architectural detail and poetic effects of light and atmosphere, he created images of compelling visionary intensity.

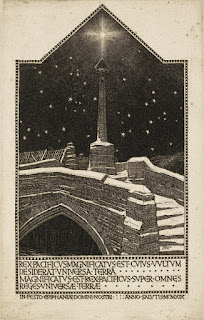

These are the Ashmolean Museum’s words (from the Introduction to a travelling exhibition, FL Griggs: Visions of England). They offer an impressive endorsement of an artist who was a significant figure in the Arts & Crafts movement 100 years ago; today, however, his is a less familiar name than the Whalls, Gimsons and Barnsleys who were his contemporaries. Something of Griggs’ ‘compelling visionary intensity’ can be seen in the strange Christmas card image* he engraved in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. It’s strange because it asks all sorts of questions: ‘Is this really a Christmas card at all?’, ‘Why so much Latin at the bottom of the picture?’, ‘Where is this odd-looking bridge and is there really a war memorial cross on top of it?’

Certainly it presents a winter scene: the artist makes full use of the black-and-white limitations of etching to highlight the snow lying on the bridge’s steps and parapets as well as on the plinth of the cross. The starry sky suggests a frosty night, but really only the blazing star at the apex of the framed image hints at Christmas – and even this is ambiguous because the beams of light from the star resolve themselves into a cross that hovers above the gabled crucifix. At the very least, you’d want to say this Christmas card almost perversely prefigures the Passion of Christ.

To add to the complication, the Latin text below the frame of the etching –

IN· FESTO· EPIPHANIÆ· DOMINI· NOSTRI· ANNO· SALUTIS· MCMXIX

On the Feast of the Epiphany of our Lord in the Year of Salvation 1919

– clearly implies that this is intended as an Epiphany card for 6th January, Twelfth night, the end of the Christmas period. Even this, however, is at odds with the framed Latin text:

REX PACIFICUS MAGNIFICATUS EST CUIUS VULTUM DESIDERAT UNIVERSA TERRA

The King of Peace is Glorified, the Sight of whose Face is the Desire

of the Whole Earth

MAGNIFICATUS EST REX PACIFICUS SUPER OMNES REGES UNIVERSÆ TERRÆ

The King of Peace is Glorified Above All the Kings of the Whole Earth

These are the words of the first Antiphon traditionally sung in the pre-Reformation Church in England – as also, of course, throughout the Catholic Church worldwide – to inaugurate the Vigil of [i.e. the night leading up to] Christmas. In 1919, however, you would have been unlikely to recognise their particular relevance unless you were a devout Roman Catholic, as Griggs had recently become, or had an antiquarian interest in the Latin texts of Gregorian plainchant. But the idea of The King of Peace would have resonated powerfully with many people at the first Christmastide after the Armistice.

Griggs himself seems to be gesturing to the war and its aftermath, both with the houses reduced to ruins beyond the bridge and with what looks like a war memorial cross (though very few of these had yet been erected). The war memorial cross in Chipping Campden, where Griggs lived, was soon to be designed by him, though not without controversy: local voices were raised against the choice of an artist who had unpatriotically (so it must have seemed at the time) abandoned the Church of England. But the memorial Griggs created bears more than a passing resemblance to the Cross on the bridge on his Christmas (or Epiphany) card. It was unveiled in 1921 and stands in the High Street close to the Market Hall.

Which leaves the question, where is the odd-looking bridge that Griggs chose as the setting for the Cross? Certainly not in Chipping Campden; in fact, this is the unique three-way, triple-arched Trinity Bridge in Crowland, the small fenland town famous for housing the ruins of Croyland Abbey, which had once been celebrated throughout Europe as a centre of learning and Benedictine monasticism. But why should Griggs have chosen Crowland? Well, for one thing he had recently been exploring south Lincolnshire, producing a series of illustrations for the Lincolnshire volume of the then very popular Highways and Byways of England travel guides; in the first edition (1926), his illustration of the bridge appears on page 490.

There is, I think, another reason. I began by quoting from FL Griggs: Visions of England. From the same source comes this:

His profound faith reinforced his deep-seated love of the countryside and medieval architecture. He increasingly lamented England’s lost identity as a result of the Reformation of the sixteenth century, the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth, and the modern dissolution of community, accelerated by the horrors of the First World War in the twentieth.

Crowland, with its ancient bridge left high and dry when the River Welland was diverted away from the towncentre, and with its ruined Abbey that had embodied everything Catholic faith and culture once stood for, perfectly enshrines Griggs’ sense of an almost lost England. Far from a conventional Christmas card, therefore, the artist’s bleak midwinter scene evokes images and ideas of light and darkness, peace and war, Christmas and Crucifixion, memorial and loss. It speaks eloquently of his anxiety for the future even as he tries to recreate an image of the precious past. For Griggs knew something almost no one now knows: that once, in medieval times, there stood on top of Crowland’s bridge a tall wayside cross – which vanished long ago.

Crowland, with its ancient bridge left high and dry when the River Welland was diverted away from the towncentre, and with its ruined Abbey that had embodied everything Catholic faith and culture once stood for, perfectly enshrines Griggs’ sense of an almost lost England. Far from a conventional Christmas card, therefore, the artist’s bleak midwinter scene evokes images and ideas of light and darkness, peace and war, Christmas and Crucifixion, memorial and loss. It speaks eloquently of his anxiety for the future even as he tries to recreate an image of the precious past. For Griggs knew something almost no one now knows: that once, in medieval times, there stood on top of Crowland’s bridge a tall wayside cross – which vanished long ago.

Adrian Barlow

*I first came across Griggs and this image when listening to a Zoom lecture last November on Arts & Crafts war memorials in the Cotswolds. I am grateful to Kirsty Hartsiotis, who gave that lecture to the Friends of The Wilson, for information about FL Griggs and the background to this image, which is catalogued as item 1990.132 in The Wilson’s catalogue. The image is © Cheltenham Borough Council and The Cheltenham Trust.

More excellent and informative reading - thank you, Adrian. More please!

ReplyDeleteAbove all, I'd like to echo Tomd's comment!

ReplyDeleteWhat a fascinating figure Griggs was. So many of his etchings communicate that mourning for a lost England – or a longing for an idealised England that can never have been quite as good as he wanted it to have been. They're haunting images and even setting aside the inscriptions this one must be mysterious too to those who don't know about the Crowland bridge and think it's something out of the artist's imagination – trust you, Adrian, to recognise it.

When Griggs began to work on the Highways and Byways series, he made ink drawings, which the printer reproduced. This was clearly a medium more similar to his art as an etcher than, say, pencil, and the results are very like his etchings. Some show details as fine as individual stones in walls and tiles on roofs; Griggs' attention to light and shade is meticulous. However, all this fine detail took time, and Griggs was always late delivering his drawings. If I remember rightly, the publishers (Macmillan) cut the number of illustrations in one book (and reduced the artist's fee) to get it done quickly. For his later volumes, Griggs used pencil, in which he could work faster – but results are neither quite as good in my opinion, nor as sympathetic to reproduction.

The most interesting piece I've read all Christmas! Thank you Adrian. I feel a further study of this interesting man and his images may be forthcoming from your pen perhaps?!!

ReplyDeleteFascinating. A bridge with no river below - I feel a visit to Crowland is warranted!

ReplyDelete