Flying, the other day, over the strange

landscape of the Gobi desert, I must have dozed off. I remember waking with a

start to see Strasbourg Cathedral being blown up. I thought at first it must

have been ‘breaking news’: some terrorist outrage streamed by CNN to the little

screen on the back of the aircraft seat in front of me. It took a while to

realize I had not been watching the News at all, but the latest Sherlock Holmes

film, proudly presented as in-flight entertainment by China Air. Even so it was

a shock: Strasbourg’s west front is one of the architectural masterpieces of

the western world – and of the Eastern, come to that.

Working in Strasbourg this weekend, I’ve

been glad to reassure myself that the Cathedral is still intact; better still,

to see that the stained glass of the South aisle has just been conserved and

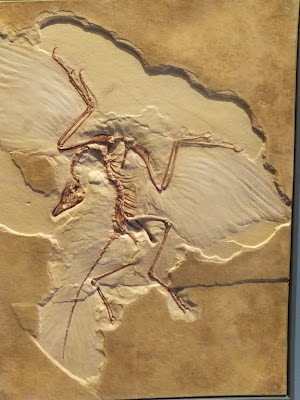

re-leaded. I had forgotten how stunning it is. In particular, I’d forgotten (I

first came to Strasbourg in 1986, and this has been my fourth visit in twenty-five

years) the marvellous colours and the sheer imagination of the artist. Look at

this image of the red-eyed Devil, early 14th century but almost as though appearing last year in a Dr. Who Christmas Show.

What I had really hoped to see on my flying

visit to the capital of Alsace was not stained glass, however, but storks.

Thomas Hardy wrote about them when he set a scene from his novel The Laodicean in Strasbourg and I wanted

to see them for myself. Every souvenir shop in the city sells toy storks –

plastic, inflatable, or plaster-of-Paris -

but I have never seen them. ‘Get up early and see them flying over the

Cathedral,’ I was told at my hotel. ‘Get the tram out to the European Court of

Human Rights; they nest over there,’ I was assured by a friend.

I tried both, but no luck. At six on a

Sunday morning only the swifts were up, practising close formation flying

around the extraordinary North Spire of Notre Dame. I love swifts, and can

watch them for hours in summer but, in almost every way you can imagine, swifts

are the opposite of storks. I took a tram and headed out past the Place de la

République in the direction of what my map called the Institutions Européennes, but again no luck.

However, on the tram itself I did encounter

a different prize specimen. Sitting opposite me was an American who wasn’t

happy, not at all. 'I’m not staying in this town,’ he announced as if into

thin air, but actually into his phone, ‘Strasbourg sucks. It’s got no water,’

(we were crossing the river as he spoke), you can’t get a decent burger, and

its just a heap of ugly buildings.’ I

suppose ugliness is in the eye of the beholder, but Strasbourg is a World

Heritage site, and the kind of city where you just want to wander, and enjoy

the narrow streets, the encircling river, the squares and the half-timbered

jettied houses – colombage, since we’re in France, but fachwerk in Germany, as Strasbourg was when these houses were

built.

You confront Strasbourg’s contested past at

every turn. The street names are given in both French and in local German.

Sometimes the results are surprising: the narrow rue du Tonnelet Rouge, linking the rue des Juifs and the rue des

Frères, becomes the Rotfässelgässel. Nearby, a plaque on a wall identifies

the site of the ancient Synagogue until the Massacre of the Jews in 1349. In

the Place St. Etienne there is another plaque, on the wall of the Cathedral

Choir School, which tells its own appalling story:

Every bookshop in the city (and there are

many) displays books about the German occupation of Strasbourg and the

brutalizing of the population under the Gauleiter

Robert Wagner. I find a photograph of a huge Nazi rally in the Place Kléber, the same square where Hardy’s heroine in The Laodicean, Paula Power, was reunited with her architect suitor,

Somerset, while staying at the Maison Rouge Hotel. She saw storks. Tired after her long journey to Strassburg (Hardy’s spelling reflects the city’s 19th century German identity), she is gazing out of her hotel window and looking at the birds through a binocular (sic): ‘ "What strange and philosophical creatures storks are," she said. "They give a taciturn, ghostly character to the whole town." The birds were crossing and recrossing the field of the glass in their flight hither and thither between the Strassburg chimneys, their sad, grey forms sharply outlined against the sky, and their skinny legs showing beneath like the limbs of dead martyrs in Crivelli’s emaciated imaginings. The indifference of these birds to all that was going on beneath them impressed her: to harmonize with their solemn and silent movements the houses beneath should have been deserted, and grass growing in streets. '

Smaller, more welcoming than Kleber Platz (as Hardy called it), is Broglie.

Not so much a square as a long oblong, it has an avenue of regimented plane

trees through the middle, leading to a memorial to General Leclerq, the ‘Liberator’

of Strasbourg in November 1944. Leclerq, who was to die only three years later

in Algeria, stands at the foot of an obelisk looking slightly self-conscious –

as well he might for he is flanked on either side by angels in flight. It’s a

curiously old-fashioned monument, almost medieval in its symbolism –

practically the apotheosis of the Maréchal de France.

But French memorials of World War II often

have difficult stories to tell, and the language for these stories is not

always easy to speak. Strasbourg endured horrors between 1942 and the end of

the War – and even for long afterwards, for many of its men were sent either to

be forced labour or to fight on the Russian front. Those who survived took a

long time to come home.

And I know of no memorial in Britain, from

either world war, which has to tell a story anything like that of the

Strasbourg City memorial in the gardens of the Place de la République. Much larger than life-size, an Alsacienne mother cradles

in her arms not one but two dying sons. It is a kind of double Pietà, and indeed the mother looks part Mary, mother of Jesus, and part

Marianne, heroine of France. But even this is to oversimplify, for the son under

one arm represents the youth of Alsace killed in the Great War fighting for

Germany against France, while the youth under the other represents the young

men of Alsace-Lorraine (which Germany ceded to France under the Treaty of

Versailles) killed fighting for France against Germany. The bodies of the two

men twist away, unable to look each other in the eye, but - almost unnoticed at

the bottom of the sculpture - their hands are clasped together.

And I know of no memorial in Britain, from

either world war, which has to tell a story anything like that of the

Strasbourg City memorial in the gardens of the Place de la République. Much larger than life-size, an Alsacienne mother cradles

in her arms not one but two dying sons. It is a kind of double Pietà, and indeed the mother looks part Mary, mother of Jesus, and part

Marianne, heroine of France. But even this is to oversimplify, for the son under

one arm represents the youth of Alsace killed in the Great War fighting for

Germany against France, while the youth under the other represents the young

men of Alsace-Lorraine (which Germany ceded to France under the Treaty of

Versailles) killed fighting for France against Germany. The bodies of the two

men twist away, unable to look each other in the eye, but - almost unnoticed at

the bottom of the sculpture - their hands are clasped together.

Adrian Barlow

[Strasbourg illustrations: (i) the North spire of the Cathedral, (ii) stained glass, early 14th century, (iii) ‘La Main Noire’ memorial, Place St. Etienne; (iv) memorial to General Leclerq, Broglie; (v) War Memorial ‘A Nos Morts’; Place de La République. Photographs by the author.

I shall be giving a lecture on war memorials, ‘Memory, Remembrance and Memorialising’ as part of the programme of War memorials: Remembrance and Community at the Oxford University Department of Continuing Education on 27 October.