In the twenties and thirties, Margaret and Paul travelled much between various places both in England and abroad, but they kept their London flat as a pied à terre, where the view from their north-facing sitting room window fascinated Nash. This view was the subject of a series of oil paintings and drawings dating from 1927 until 1934, by which time their view of Sir George Gilbert Scott’s masterpiece – the Midland Grand Hotel that acts as a façade to the station behind – had been entirely blocked by the recently erected Camden Town Hall.

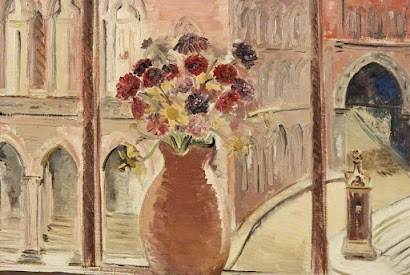

St. Pancras, London (1927), which belongs to The Wilson, Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum, is probably the earliest and certainly the most intimate of these images. At first glimpse indeed it seems almost touchingly simple: a jaunty bunch of small flowers, though of rather muted colours, sits in an earthenware jug placed up against a sash window. Through the panes of this window can be seen, on the left, the entrance to the steps leading to the Midland Grand Hotel’s main entrance and, on the right, the sweep of the drive turning off the Euston Road towards the arch through which taxis could convey their fares up to the ticket office of the old station. The view is entirely devoid of people or vehicles. Only the flowers and the sash window stand between Paul Nash and all stations to Bedfordshire, though nowadays of course it is the London terminus for Eurostar.

The flowers themselves reflect all the colours used by the artist to paint the building across the road; or should that be vice versa, for what really is the subject of the painting? Its title suggests the station, but without the title, wouldn’t one call this a still life: jug of flowers, window, distant view? The building in the background is, frankly, only lightly sketched.

As Nash has painted this picture, you’d think the window of Flat 176 must have looked straight out across the Euston Road towards the entrance to the station forecourt. It is worth noting that the only architectural feature painted in any detail is the smallest but also the one closest to the artist: the carved stone finial on top of the single gatepost. You can tell from the slight angle of the window frame that Paul Nash was not standing exactly in front, but to the right, of the jug of flowers: as he looked out, he must have been standing square on to the gatepost.

But Queen Alexandra Mansions do not stand directly opposite St Pancras – and never did. When Nash and his wife gazed out of their window they looked across Bidborough Street, over the roof of an undertaker’s premises and down onto some small gardens which bordered Euston Road. But for Nash in 1927 it was as if none of that got in the way.

Only in 1929 when the coffin shop was demolished and the gardens were cleared to make way for

hoardings to enclose the space where the new town hall was to be built, did Paul and Margaret Nash feel a sense of impending loss. In that year he abandoned the still life and the sash window. Instead he stared with growing dismay straight at the increasingly surreal scene unfolding before him: skeletal billboards being erected; high hoardings presenting a barrier between him and the architecture that had so fascinated him. Signs of decay began to appear – an outsize window from the hotel façade lying at a crazy angle, the footpath leading up to the arch now reimagined as a sleek silvery tongue; only the solitary gatepost with its trefoliated finial still standing as a reminder of how things used to be. Nash painted all this in Northern Adventure (1929), a picture that stands in stark opposition to St Pancras, London.Looked at another way, you could argue that the St Pancras building now looks like a flimsy stage set ready to be dismantled, its walls no more than painted canvas and the discarded window outside just one more prop to be stored away. Nash’s own window, the window of the flat he shared with his wife in Queen Alexandra Mansions, has also been discarded: in this picture, it simply doesn’t appear.

Eventually, when Camden Town Hall had risen to block their view of St Pancras entirely, it was time for Margaret and Paul to move. They gave up their flat in 1934. Today there is a blue plaque to commemorate Paul’s time living in Queen Alexandra Mansions, but of Margaret (whom Paul always called Bunty) there is no mention. Which is a shame, for she was a remarkable woman in her own right.

Footnote

I have never lived in London. I doubt if I have ever spent more than three consecutive nights in the city, but I know my way around some parts pretty well, especially the Euston Road, St Pancras and Kings Cross areas. These are the stations where – at different times of my life – I have arrived and departed from or to Birmingham, Durham, Bedfordshire, Cambridge and Paris. And, as it happens, I know Queen Alexandra Mansions well, too, because one of my oldest friends, Mary Whitty, lived there for many years. Like Margaret Odeh, Mary was a remarkable woman with wide interests, a strong sense of social justice and a love of art, literature and travel. She was always loyal to her friends. Had she and Paul Nash’s wife been neighbours in Queen Alexandra Mansions, I think they would have got on well. Mary died in 2018, and is much missed by many people.

Adrian Barlow

This post is an expanded version of my account of Paul Nash’s painting, St. Pancras, London, which you can read on the website of the Friends of The Wilson, Cheltenham Museum and Art Gallery.

I recommend an excellent blog, Inexpensive Progress, written by Robjn Cantus. This includes a fully illustrated essay about Paul Nash and St. Pancras, which has provided some of the information I have included above.

I have written before about King’s Cross and St. Pancras: