In June 1915, the War in France not yet a

year old, Thomas Hardy visited Exeter with his second wife, Florence. They went

to a concert and then, next morning, visited the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, where a

particular exhibit caught Hardy’s attention and spurred him to write ‘In a

Museum’. It’s a poem crying out for some context.

I

Here's the mould of a

musical bird long passed from light,

Which over the earth before

man came was winging;

There's a contralto voice I

heard last night,

That lodges with me still

in its sweet singing.

II

Such a dream is Time that

the coo of this ancient bird

Has perished not, but is

blent, or will be blending

Mid visionless wilds of

space with the voice that I heard,

In the full-fledged song of

the universe unending.

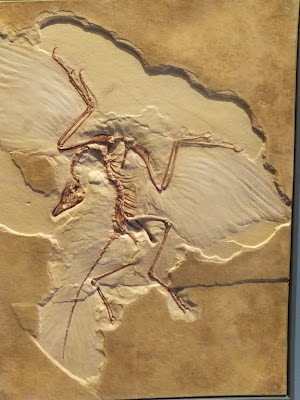

The exhibit he writes about in this poem is

a plaster cast (‘mould’) of a fossil of the earliest known bird, archaeopteryx. The original had been

found in Germany only a few years after the publication of The Origin of Species, and was hailed as evidence to support

Darwin’s theories because it was a transitional fossil, one that suggests birds

may have evolved from dinosaurs.

Extinct birds aren’t unusual museum

exhibits: there is a fine specimen of a stuffed dodo – fine at least if you

don’t have (as I have) an aversion to taxidermy – at the Horniman

Museum in South London. But this bird puts the dodo in the shade: it was

flying ‘over the earth’ long before the late appearance of homo sapiens. ‘Winging’ may sound slightly precious. However, Hardy

needs it to prepare for the feminine rhyme ‘singing’ at the end of the stanza; and

the word also echoes the name of the bird itself: the Greek etymology of archaeopteryx is ‘ancient wing’.

The fossil, though millions of years old,

is present to the poet ‘Here’ and now. Similarly, the beautiful voice he heard

last night is simultaneously in the past – ‘There’ – and present because it

‘lodges with me still’. The poet is moved by song, whether it be the ‘sweet’ contralto

voice of the singer or the ‘coo’ of the musical bird. He himself enjoys the

music of poetry: he lays on alliteration enough in the first line (‘mould /

musical … long / light) and the rhythms of the long, leisurely lines are

carefully modulated, no one line quite mirroring another.

But if Hardy in the first stanza focuses sharply

on the here and now, in the second he adopts a longer perspective: ‘Such a

dream is Time’ that past and present are arbitrary and elastic. The ‘coo’ of

the archaeopteryx has either been already ‘blent’ (a word Philip Larkin later

borrowed for ‘Church

Going’) - into the song of last

night’s singer, or it will ‘be blending in the future. Time is as limitless as

the prehistoric landscape over which the bird flies is ‘visionless’. It is as

unimaginable and as incommunicable as the strange arctic birds who visit Tess

of the d’Urbvervilles:

gaunt spectral creatures with tragical eyes –

eyes which had witnessed scenes of cataclysmal horror in inaccessible polar

regions of a magnitude such as no human being had ever conceived …. But of all they had seen which humanity

would never see, they brought no account, The traveller’s ambition to tell was

not theirs. (Tess of the d’Urbervilles,

Ch. XLIII)

This is one of Hardy’s bleakest images of

man’s cosmic insignificance. ‘In a Museum’, by contrast, is more ambiguous. ‘The

full-fledged song of the universe unending’ recalls Keats’s nightingale whose singing

with ‘full-throated ease’ draws the speaker towards ‘easeful death’. But is

this indeed a poem about human insignificance in a universe as indifferent to

man as the strange birds were indifferent to Tess? Or is ‘full-fledged’ in fact

an affirmative epithet, pointing us towards the idea of celestial harmony and

the music of the spheres – a harmony and a music of which man is a part?

Besides, what exactly is unending? The song

or the universe? Whichever it is, does the word invite us to contemplate bleak

endlessness or hopeful continuity? In ‘The Voice’ – a poem

written only a year or two before ‘In a Museum’, Hardy had wondered whether the

voice that was calling to him really was the voice of his dead first wife,

Emma, or just a trick of the wind,

You being ever

dissolved to wan wistlessness

Heard no more

again, far or near?’

In the end, though, despite his doubts he stubbornly

insists the voice is that of ‘the woman calling’. My own reading of ‘In a

Museum’ is that while Hardy leaves the question open, the positioning of ‘unending’

as the last word of the poem, and the stress on the prefix ‘un-’ allows at least

the possibility of hope. ‘Un-’ can indicate joy, after all: unconfined, unalloyed.

‘Unending’ is a more positive word than ‘endless’, carrying none of the

desolation of ‘wistlessness’ or (Hardy’s original choice of word in ‘The Voice’)

‘existlessness’.

Not everyone agrees. Some critics see this

poem as a clear statement of his pessimism. But the second line of the second

stanza – ‘perished not … blent … will be blending’ seems to me affirmative, a

case at least of Hardy’s ‘hoping it might be so’. I don’t think I’m alone in

thinking this. Seamus Heaney’s sonnet sequence, The Tollund Man in Springtime, has a remarkable poem about

resurrection and recreation which ends in a homage to Hardy:

Then, when I felt the air,

I was like

turned turf in the breath of God,

Bog-bodied, on

the sixth day, brown and bare,

And, at the

last, all told, unatrophied.

Hardy famously liked inventing adjectives

prefaced by ‘un-’. (The key scene in Alan

Bennett’s The History Boys , where

Hector dissects Hardy’s poem ‘Drummer Hodge’, hinges on this). ‘In a Museum’ is

ultimately about how ‘the coo of the ancient bird’ hasn’t atrophied either.

A terrific blogpost. As luck would have it, I went to a talk on Hardy and Devon by my colleague Angelique Richardson a fortnight ago, and she mentioned this poem. Somehow it had escaped my attention previously.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteMany thanks, Tim. There is a challenging article by Catherine Lanone, ‘Mechanical Birds and Shapes of Ice: Hardy’s vision of the Blind Watchmaker’, which takes a rather bleaker viewer of the poem than I do, but which I found stimulating and well worth recommending. You can access it at

Deletehttp://www.miranda-ejournal.eu/1/miranda/article.pdf?numero=1&id_article=article_17-815

Another fascinating treatment of a single poem.

ReplyDeleteI was always interested in Larkin's adoption of the word "blent" in the poem Church Going. I haven't seen it elsewhere until you drew my attention to Hardy's poem.

In Larkins' hands, it seems to define the atmosphere of "a serious house on serious earth" in which each of our destinies is processed and finally consigned to the grave and therefore to eternity. Not far away, then, from Hardy's unending universe in this poem.

Perhaps no suprise, for as poet Sean O'Brien points out, "..it still seems true that Thomas Hardy was the most important imaginative trigger for Larkin's discovery of what he could do on his own account...." (TLS, June 8 2012).